Introduction

If you have used Bitcoin, Ethereum or any other cryptocurrency you would be familiar with public and private keys and if you are a more savvy person you might have also heard about ECC(Elliptic Curve Cryptography) or ECDSA(Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm). Today we will find out what exactly ECC is and how and why it’s used in case of Bitcoin and maybe other cryptocurrencies.

Brief History on Public-Key Cryptography

Public key cryptography is not new, it’s been around for a long time. The first public key cryptography algorithm was Diffie-Hellman. ECC is just one way of doing public-key cryptography. It was invented by two guys named Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman. Apparently Hellman was obsessed with the problem of how do I send my friend an encrypted message? Well it’s easy to send the encrypted message but how do I send the decryption key to the encrypted message. I could encrypt the decryption key, but then how do I send him the key to decrypt the decryption key? As you can see this quickly becomes a recursive problem that never ends. Hellman then teamed up with Diffie and went across the country to meet him. After approximately 4 years, in 1976 they came up with the Diffie–Hellman key exchange algorithm. So Diffie-Hellman is first of it’s kind. There are several others now, to name a few there are ElGamal, Paillier cryptosystem and RSA.

Fun fact: You use the RSA algorithm in your daily life because the HTTPS protocol uses RSA encryption. Without HTTPS your WhatsApp conversations wouldn’t be secure(not that they are secure to begin with because your data is getting zucked by Facebook, but at least people near you can’t see the data in clear text) and web security in general would be a security nightmare.

Properties of Public-Key Cryptography Systems

Why does Bitcoin use asymmetric-key cryptography? Well, asymmetric keys offer 2 properties:

Public and private keys - unlike symmetric-key cryptography you have a private and a public key - the public key is used to identify you publicly and the private key, as the name implies is kept safe. If your private key is lost or compromised then the attacker has full control over you funds. Also note that it’s computationally unfeasible to work your way back to a private key given a public key. Functions that have this characteristic, easy to compute one way but hard to compute the other way, are called Trapdoor functions. More formally, given a function

f(x)it’s hard to findf’(x).Sign and verify messages - this lets you prove that you are the owner of the corresponding public key without actually giving away the private key. This lets you sign transactions which is then verified by the miners that the transaction actually came from you.

Okay enough talk, let’s dive into the mathematics of elliptic curves.

Elliptic Curves

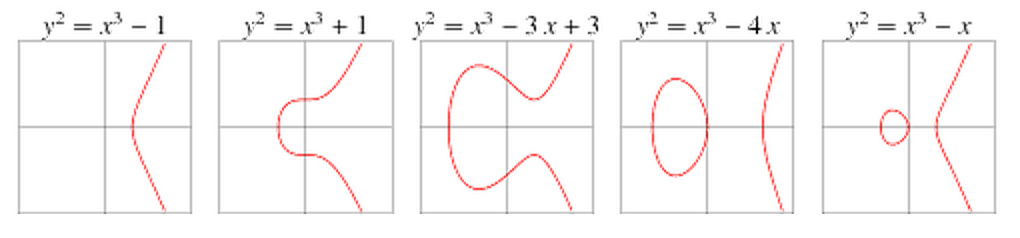

Elliptic curves generally have a mathematical form of y2 = x3 + ax +

b. Your public key is just a point on this curve. In case of Bitcoin, it uses a standard

called secp256k1 in which a=0 and b=7 so the equation ends

up as y2 = x3 + 7. See Bitcoin

wiki for more info.

Elliptic curves are symmetric along their x-axis - this means that given point x on the x-axis,

the corresponding points on the y-axis are y and -y. This property is smartly used in Bitcoin

addresses to save transaction fees. Originally Bitcoin used “uncompressed” public keys in which your

public key is both the x and y coordinate of a point. But later, using this property, it

introduced a new “compressed” key format that lets you save data (as the public key is reduced to

half of it’s size by omitting the y coordinate) and thus save transaction fees. See

bitcoin-book

on how compressed keys are represented.

Elliptic Curves over a Finite Field:

Bitcoin public keys are computed by multiplying a base

point, usually denoted by G, that is

known to everybody times your private key (a 256-bit number). When you multiply a point P on the

curve by a number n, it is not always guaranteed to be less than 2256. Why should it be

less than 2256 you ask? Well there are always standards, or more like limits, on how big

the number can be (depending on the use-case). In case of Bitcoin and most other use cases the limit

is 2256. Bitcoin’s public keys are 512 bits long (256 for the x-coordinate and 256 for

the y-coordinate).

Note: I’m only talking about the points associated with an uncompressed public key, the actual public keys are more than 512 bits long, this is because you encode some information to the key along with the points.

So in order for the public keys to fit the 512 bit length obviously each coordinate should be less

than or equal to 2256. So how do we ensure that the computed number is always less than

2256? The answer is that we compute the Elliptic Curve over a finite field. Finite Fields

are beyond the scope of this article so if you don’t know what finite fields are then

this would be a good place to start. To be frank even

I don’t know finite fields to it’s core, but I got the basics down. Calculating Elliptic Curves over

a finite field would make sure that the computed number is always less then 2256. A naive

explanation of finite fields would be that we take the mod of the result computed with respect to a

number p. This number p is usually prime. In case of secp256k1 p is the largest prime number

that is less than 2256.

Point Operations on Elliptic Curve

Point Addition

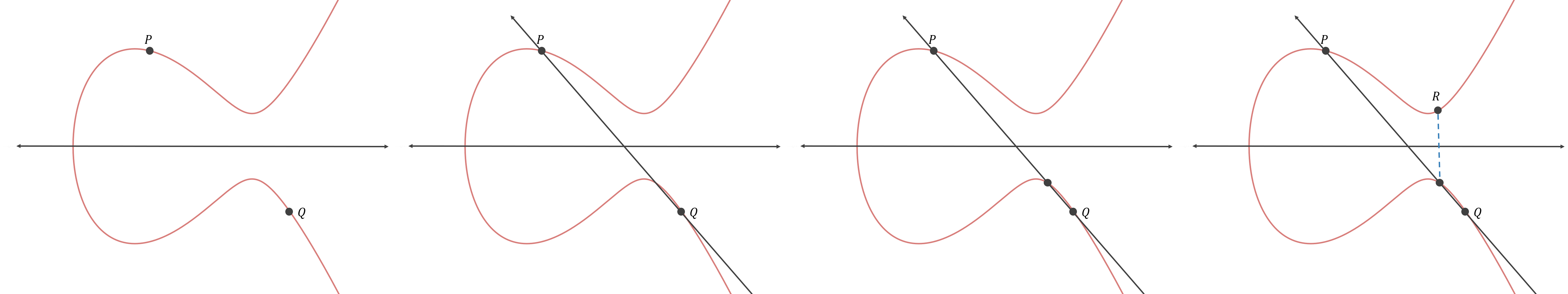

Lets say you have 2 points P and Q on the elliptic curve E and you need to add these two

points. How do you add two points on the elliptic curve? It turns out that you need to find a line

L that’s passing through these 2 points. Once you have done that, you have to find another point

R at which the line L intersects the curve, usually denoted by E. You then reflect that point

R about x-axis, i.e flip the sign of y-coordinate of the point. This point is our 3rd point R

that we get by adding the 2 points P and Q. Lets visually see what’s going on. Images are taken

from this hackernoon

article.

Mathematically adding is given as follows: (taken from wikipedia)

slope = (Q[y] – P[y]) / (Q[x] – P[x]) mod p # finite fields R[x] = slope2 – P[x] – Q[x] mod p R[y] = slope * (P[x] – R[x]) – P[y] mod p

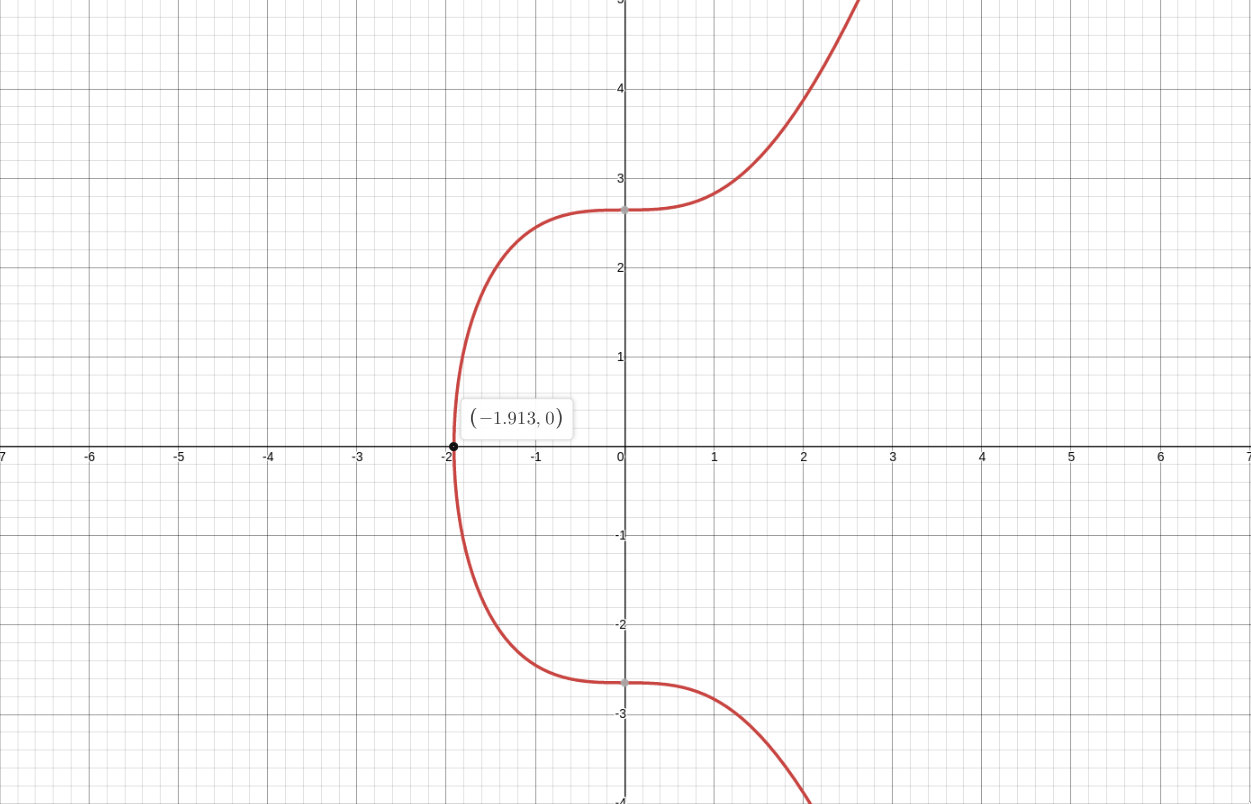

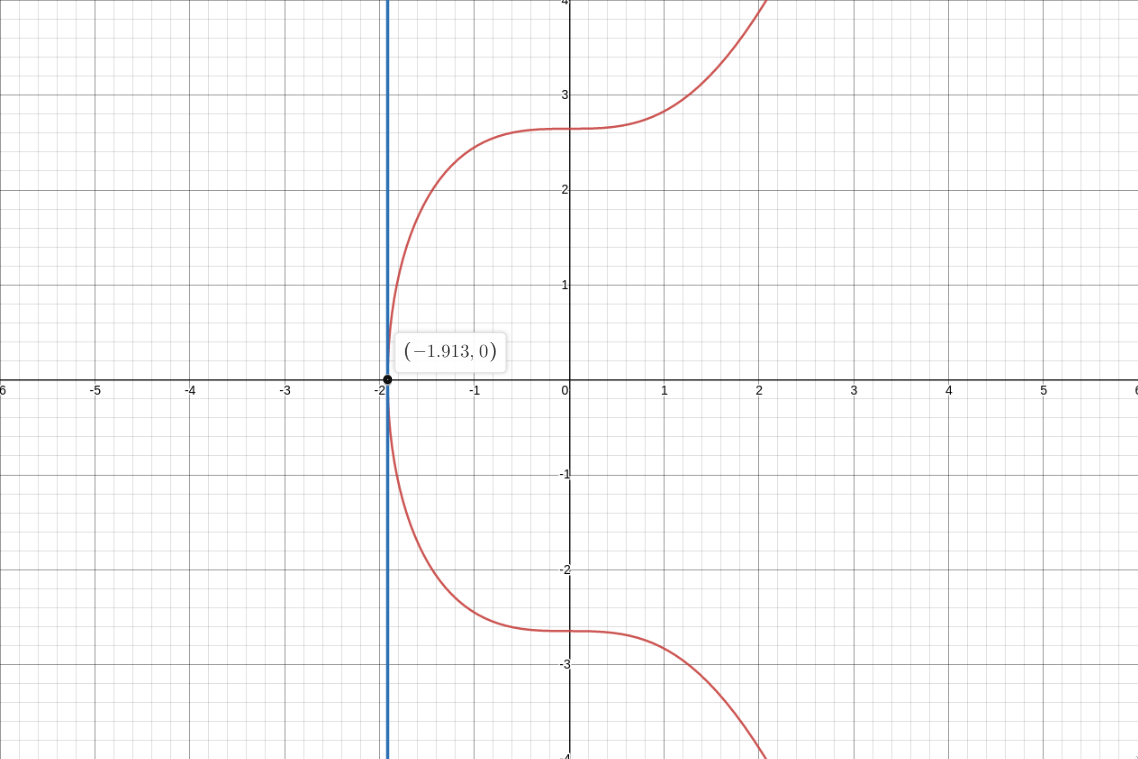

If you were paying attention you might have noticed something. Given 2 points and a line L which

passes through those 2 points, it is not always guaranteed that the line L will intersect the

curve at a 3rd point. Now that you know that it will not always intersect the curve at a 3rd point,

I’d like you to think of a point at which this will happen. Did you find out which point it is? Yeah

it’s the point of inflection (I’m not entirely sure if it’s called the point of inflection, so I

just included an image with the point highlighted). There is also another image showing the tangent

line at that point, as you can see the slope is infinity and the line always stays parallel to the

y-axis hence it doesn’t intersect the curve at any other point (graphs are made using

desmos).

So here are few properties of the elliptic curve that you might find useful later:

- A non-vertical line intersecting two non-tangent points on the curve will always intersect the curve at a third point.

- A non-vertical line tangent to the curve at a point will intersect precisely one other point on the curve.

Note: The lines have to be non-vertical for the reasons mentioned above.

Point Doubling

Adding 2 points isn’t always the case. Sometimes you need to add a point to itself. In that case we

can’t use the above formula because we can’t find the slope of a line using just one point and

moreover there are infinite lines passing through a single point P, so which one do we choose?

Well we take the tangent line at point P. Why the tangent line you ask? Well you can still think

of it as 2 points and that point Q is approaching P (infinitesimally closer to P) and now the

line becomes the tangent line at point P. If you have taken any calculus class before you might be

familiar that the slope of an equation at any given point is given by it’s first derivative. In this

case the first derivative of y2 = x3 + ax + b is:

$$\frac{\mathrm{d}y}{\mathrm{d}x} = \frac{(3x^2 + a)}{2y}$$

Then the equation of the tangent line is given by:

$$y = mx + c \text{, where } m = \frac{(3x^2 + a)}{2y}$$

Now that we have the equation to the line, we substitute it in the equation of the curve to find

where they coincide, note that x1 and y1 are coordinates of point P.

$$[m(x - x1) + y1]^2 = x^3 + ax + b \text{, where } m = \frac{(3x^2 + a)}{2y}$$

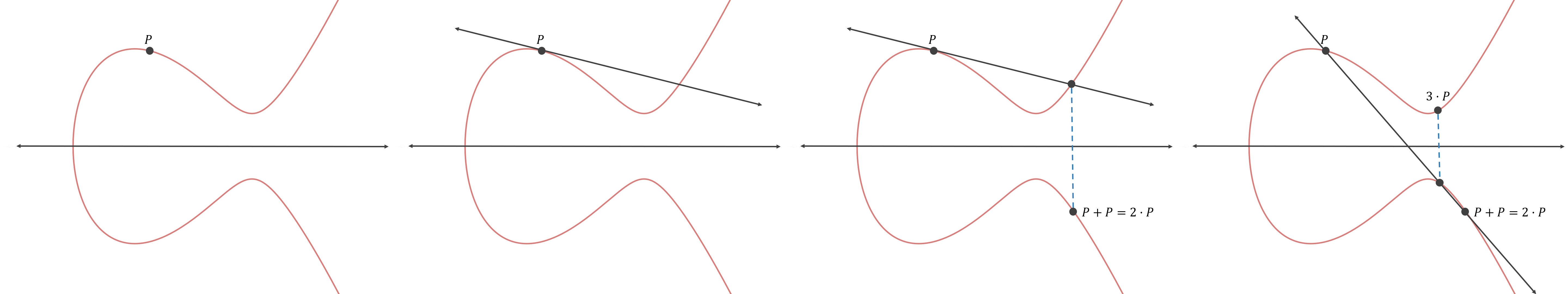

You then solve the equation to get point R. Now, let’s visualize what’s happening: (images are

taken from this hackernoon

article).

Mathematically adding is given as follows: (taken from wikipedia)

slope = (3 P[x]2 + a) / (2 P[y]) mod p R[x] = slope2 – 2P[x] mod p R[y] = slope * (P[x] – R[x]) – P[y] mod p

Point Multiplication

Okay now how do we multiply a point with a scalar? Let’s say you want to compute n * P, where n

is a scalar. A naive approach would be to add that point to itself using the point addition

algorithm n number of times. But in real life applications these numbers are humungously large so

it’s not very practical. Turns out there are multiple methods to do this, see

wikipedia

for all the different methods, in this article we focus on the double-and-add method. The algorithm

for double-and-add is as follows: (taken from

wikipedia)

def f(P, d):

if d == 0:

return 0 # computation complete

elif d == 1:

return P

elif d % 2 == 1:

return point_add(P, f(P, d - 1)) # addition when d is odd

else:

return f(point_double(P), d/2) # doubling when d is even

There is another implementation, of the same algorithm, on the wikipedia page, but I find it a little confusing. If you are a computer science student you might recognize that this algorithm is analogous to the binary exponentiation algorithm. Turns out this is exactly the same, only that we are doubling and adding instead of multiplying and squaring.

Let’s break it down a little more with an example. Let’s say you want to compute 10*P. We can

approach the problem in 2 ways:

you could add

Pto itself 10 times - P + (P + (P + (P + (P + (P + (P + (P + (P + P)))))))) oranother approach would be to calculate it this way

2P = P + P

4P = 2P + 2P

8P = 4P + 4P

10P = 2P + 8P

Clearly the 2nd approach is far better as it only uses the point addition algorithm 4 times compared

to 10 times in the first approach. Just to make thing clear here’s another example. In this example

we calculate 9*P, this time it’s more like the original algorithm:

9 = 1001 (in binary - just means 8 + 1)

R = 9 P

R = P + 8P

R = P + 2(4P)

R = P + 2(2(2P))

# we start calculating 9P here

R = P + 2(2(P + P))

R = P + 2(2P + 2P)

R = P + 4P + 4P

As you can see computing 9*P again only requires 4 point additions compared to 9 if we were to use

the naive approach.

Fun fact that you don’t need to know and is totally irrelevant: I kind of came up with this on my

own once I got to know that adding point P to itself n times is not practical (most probably

because I was already familiar with the binary exponentiation algorithm). Yeah, feels a little

validating xD.

Finally here is the python code for the above operations that I copied from stackoverflow and fixed it.

Now that we got the basics down, we can then go on and explore how digital signatures work. In the next article we will explore how Digital Signatures works. At it’s core it’s basically “tell me that you know a number without actually telling me the number”(if you get the reference, lol).

This is my first article so I don’t know how it came out. I took a ton of copied inspiration

from this hackernoon

article,

you should check it out though he did an amazing job at explaining Elliptic Curve Cryptography.

Thanks for reading.

References

- Elliptic Curve Cryptography - A Gentle Introduction

- Math behind Elliptic Curve Cryptography

- ECDSA - learnmeabitcoin

- Elliptic Curve - math.brown.edu

- Elliptic Curves from mae.ufl.edu

- Public Key - learnmeabitcoin

- Elliptic Curve - Point Multiplication

- Order of a point on an Elliptic Curve

- Intuition on point at infinity(the identity element)

- A Diffie-Hellman Primer from UCLA

- Math behind Bitcoin - Coindesk

- Elliptic Curves - arctechnica

- ECC - A gentle introduction

- Finite Fields

- modular inverse of square root algorithm - R

- modular inverse of square root algorithm - python

- modular square root